Imagine a housing market where prices are out of reach, banks tighten loans, and the government steps in. Sound like 2024? It was actually 33 AD.

The Roman Real Estate Boom

Before the financial collapse of 33 AD, Rome was experiencing what could be described as a speculative property frenzy. With the empire expanding and provincial wealth flowing into the capital, Rome’s elite turned increasingly to land as their preferred asset—mirroring today’s belief in real estate as a safe and appreciating investment.

In Roman society, land ownership was more than just profitable—it was political. Property conferred status, voting power, and eligibility for public office. For senators, equestrians, and wealthy merchants, accumulating land wasn’t merely an investment strategy; it was a social necessity.

But this wasn’t just about building villas. Land served as a store of value in an economy often subject to monetary fluctuations. With no central bank, inflation and coinage debasement were real risks, and tangible assets like land offered a hedge. Add to that the lack of regulatory oversight—no restrictions on mortgage leverage, insider speculation, or monopolistic accumulation—and speculative bubbles were all but inevitable.

Rome’s wealthy class poured capital into rural estates across Italy, inflating prices and creating what we might now call a “real estate asset bubble.” And like many bubbles, it was sustained not by need, but by expectation: the belief that land values would always rise, and that selling would always be easy—until it wasn’t.

Easy Credit Fuels the Fire

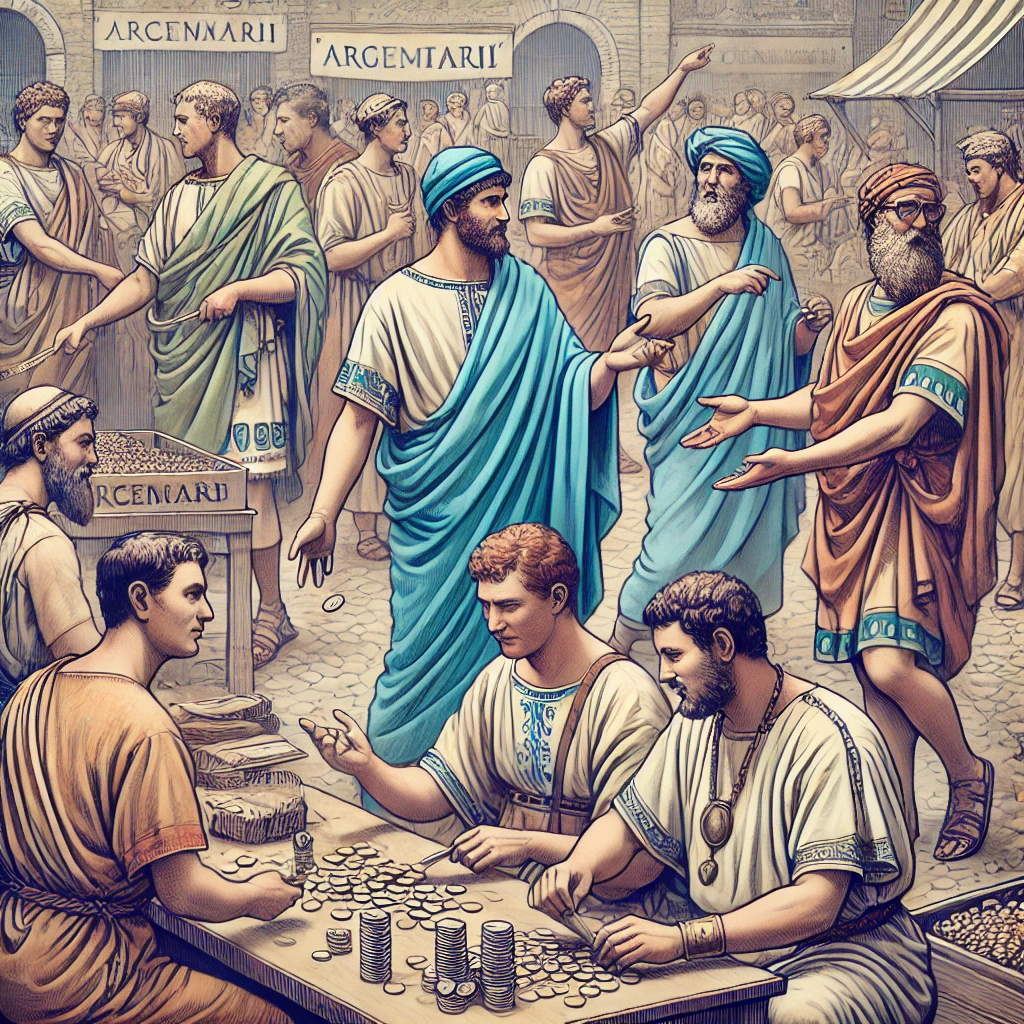

Access to credit in early 1st-century Rome was surprisingly fluid—perhaps dangerously so. Wealthy elites often borrowed vast sums to acquire additional estates, pledging their existing properties as collateral. This procyclical lending—borrowing more as asset values rose—amplified the expansion of the real estate market.

Moneylenders (argentarii), including senators and high-ranking officials, actively participated in these leverage loops, re-lending and refinancing in ways that closely resemble modern credit bubbles. There were few checks on who could lend, how much could be borrowed, or what reserves were required. Interest rates, while unregulated, are known to have reached 12% annually or more, depending on risk and status—remarkably high given the supposed stability of Roman aristocratic borrowers.

Critically, Rome lacked any form of central monetary authority. No central bank. No lender of last resort. No unified oversight. In this vacuum, credit expansion continued unchecked—until confidence faltered.

As long as land prices kept climbing, this fragile system worked. But it was an illusion of stability: a real estate market built not on fundamentals, but on speculation and the expectation of perpetual growth. Rome wasn’t just expanding its frontiers—it was inflating a bubble, with debt as its fuel.

The Economic Boom Under Augustus: The Real Estate Bubble and the Path to Crisis

Under Augustus, Rome entered a period of rapid growth and relative stability, thanks to both military expansion and the Pax Romana’s political consolidation. To secure legitimacy and popular support, Augustus pursued ambitious fiscal policies, including large-scale public works, distributions of grain and cash to citizens, and veterans’ settlements—actions that stimulated aggregate demand and increased money circulation across the empire.

Credit conditions also loosened. Although Rome lacked formal banking regulation, informal lending expanded during this era, especially as public spending enriched artisans, freedmen, and contractors who worked on imperial infrastructure projects. Many of these newly affluent groups turned to land as a store of value and a path to social mobility—mimicking the traditional habits of the senatorial elite.

Land ownership wasn’t just a safe investment; it was a gateway to prestige, voting rights, and political leverage. As prices climbed, both established patricians and emerging classes began speculating in real estate, fueling a feedback loop: rising prices encouraged further purchases, often financed by debt, which in turn pushed prices even higher.

This created an illusion of permanent prosperity. But unlike modern economies with central reserves and counter-cyclical tools, the Roman state lacked a fiscal buffer. Augustus’s heavy front-loaded spending, combined with widespread speculative behavior and growing inequality, left the empire highly exposed to shocks—and without the monetary or institutional means to absorb a downturn.

A Law Meant to Fix It—And How It Backfired

By the 30s AD, Rome’s real estate bubble was widely acknowledged: fortunes were built on leverage, land prices soared beyond fundamentals, and the credit system grew increasingly fragile. Yet the actual trigger of the collapse wasn’t external—not a war, nor a natural disaster—but a regulatory misstep.

In 33 AD, Emperor Tiberius ordered the enforcement of an old, dormant law: the Lex Julia de pecuniis mutuis (often referred to under the broader Lex de Usuris). Originally passed under Julius Caesar, the law required that at least one-third of all loaned capital be secured by real estate located within Italy. Its goal was twofold: to anchor credit to domestic assets (preventing capital flight) and to discourage purely speculative lending.

The intention was prudent—but its retroactive and sudden enforcement proved devastating. Lenders and borrowers alike scrambled to meet the new requirement. Those holding large amounts of debt without enough Italian land had to liquidate assets rapidly to comply.

This wave of rushed sales flooded the market with properties, pushing prices downward. As valuations collapsed, so did the value of the collateral backing many loans. Banks and creditors, facing devalued assets, called in loans en masse, further drying up liquidity.

What began as a technical compliance issue quickly spiraled into a full-blown credit crunch, eerily similar to modern liquidity crises triggered by abrupt regulatory tightening—such as mark-to-market accounting during the 2008 crash or capital reserve hikes during financial shocks.

Legal Shock and Market Panic

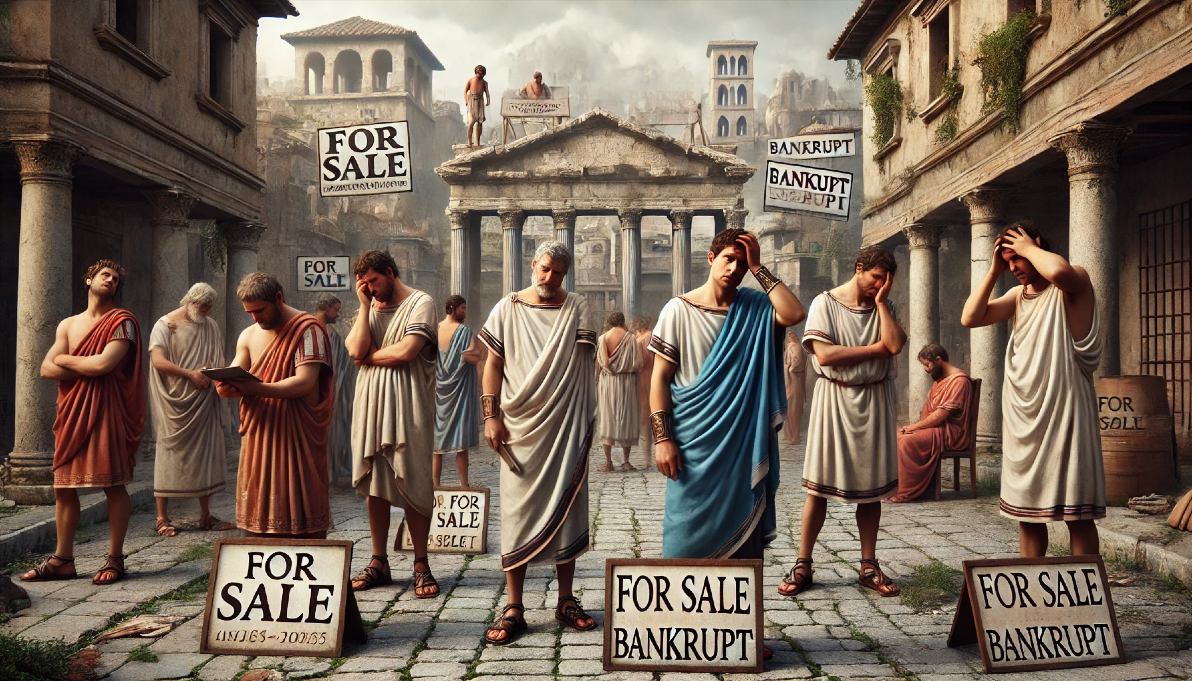

Writing years after the fact, Tacitus vividly captured the psychological and economic turmoil that swept through Rome’s financial elite. Senators—once insulated by rank and wealth—found themselves over-leveraged, illiquid, and legally exposed. In their rush to comply with the newly enforced law, many were forced to sell assets at distressed prices, only to discover that the market had no floor.

“There was panic everywhere. Creditors were pressing their claims; debtors had no means of paying…”

— Tacitus, Annals VI.16

Courts overflowed with lawsuits as credit relations unraveled. Lenders couldn’t recover loans. Borrowers couldn’t meet obligations. Real estate, once seen as a stable store of value, had become illiquid and unpriceable. Without functioning markets, no one knew what their assets—or their debts—were really worth anymore.

This is the textbook definition of a credit crunch: a rapid withdrawal of lending, triggered by collapsing asset values and the erosion of trust. In attempting to stabilize a speculative economy, Rome’s government had unintentionally punctured its own financial structure, exposing how dependent the system was on ever-rising prices and unregulated credit.

What followed was one of the earliest recorded financial contagions: a legal adjustment that became a liquidity trap, then a solvency crisis—and it wasn’t over yet.

The 33 AD Credit Crunch

As land prices collapsed and credit dried up, Rome entered a destructive financial spiral. The sell-off triggered by the reactivated lending law quickly outstripped market demand. Landowners, desperate to raise cash, couldn’t find buyers. The once-booming property market had become frozen. Banks stopped issuing new loans. Wealthy citizens, though nominally asset-rich, became functionally insolvent—unable to meet obligations or convert holdings into liquidity fast enough.

In modern economic terms, this was a textbook liquidity crisis—but with an added twist of systemic contagion. The money existed, but it ceased to circulate. As prices fell, so did the value of loan collateral. This sparked a wave of margin calls, defaults, and panic-driven fire sales—further depressing prices in a vicious loop.

The Roman elite, long accustomed to easy borrowing and opaque accounting, suddenly faced a brutal reckoning. Court dockets swelled with lawsuits over interest rates, repossessions, and insolvency proceedings. The situation was aggravated by a dangerous structural flaw: many senators and equestrians acted simultaneously as both lenders and borrowers. When one defaulted, others followed, setting off a cascade of interlinked failures.

With trust shattered, and no central institution to intervene or provide guarantees, the Roman credit system effectively collapsed.

A Confidence Crisis Without a Central Bank

Unlike modern economies, the Roman financial system lacked any form of central coordination or institutional backstop. There was no central bank to inject emergency liquidity, no lender of last resort to stabilize markets, and no fiscal authority with the flexibility or tools to implement countercyclical measures.

What Rome had instead were blunt instruments: legal edicts, symbolic gestures, and limited public lending programs. These responses, while politically visible, proved economically toothless in the face of systemic collapse. Without trust, and without intervention, the bleeding continued.

The consequences rippled far beyond the senatorial class. Smallholders, craftsmen, and provincial investors—many of whom had risen through land speculation or state contracts—were hit hard. Debts were suddenly recalled across the empire. Property values, the foundation of their newfound status, evaporated. Social mobility froze, then reversed. The very asset that had elevated them—land—now became a trap.

“The value of land had sunk; credit was nowhere to be found; and panic reigned among those who had only months before considered themselves untouchable.”

What unfolded was a textbook crisis of confidence, made worse by a policy vacuum. A law intended to restore financial discipline instead triggered a wave of forced deleveraging, collateral deflation, and social retreat. Rome had built an economy on unregulated credit expansion and inflated expectations—and when that foundation cracked, the system had no safety net.

Before 33 AD

Rapid property speculation across Italy. Credit flows freely. Land prices soar.

33 AD (Early)

The Lex de Usuris is enforced again, requiring loans to be backed by one-third Italian land.

Shortly After

Landowners rush to sell property to comply. Market floods. Prices begin to collapse.

Panic Spreads

Credit dries up. Courts are overwhelmed. Trust between lenders and borrowers evaporates.

Crisis Peaks

Land values drop dramatically. Elite Romans face bankruptcy. Social tensions rise.

Tiberius Intervenes

The emperor injects 100 million sesterces in interest-free loans to restore liquidity.

Enter Tiberius – The Interest-Free Bailout

As panic swept through Rome’s financial system and the prospect of widespread default loomed, Emperor Tiberius—known more for austerity than bold reforms—stepped in with a remarkably modern solution: a state-backed liquidity injection.

Tiberius authorized the creation of a 100 million sesterces fund, designed to provide interest-free loans for up to three years. The aim was clear: to unfreeze credit markets, restore confidence, and stop the downward spiral in land prices.

But this was no blanket stimulus. The loans came with strict conditions:

- Borrowers had to pledge land as collateral—often valued at twice the amount borrowed.

- Lenders (often elite families and bankers) were required to maintain their credit exposure, rather than liquidate positions or call in debts.

In effect, this was a targeted credit backstop, not a general bailout. It didn’t erase debts or flood the economy with new currency. Instead, it aimed to re-anchor the value of land—which served both as collateral and the core asset of elite Roman wealth.

This intervention bears similarities to modern credit easing or emergency lending facilities. Yet it also had built-in limitations: by requiring land as security, it excluded those without sufficient property—particularly smallholders, traders, and urban renters—thus stabilizing the system from the top down.

A Precedent for Modern Bailouts?

InIn today’s terms, Tiberius implemented what we might call a state-backed liquidity facility—not quite quantitative easing, but a decisive move to inject confidence into a collapsing credit system. There was no central bank in ancient Rome, no monetary policy committee, no printing press—but the core principle was familiar: restore liquidity, contain panic, and stabilize the asset base.

Historians like Tacitus noted that the intervention had a measurable effect. Credit slowly began to flow again. Lawsuits over unpaid debts eased. The worst of the panic was defused. But it was a partial recovery at best: land prices remained depressed, and many elite families—once pillars of Rome’s political and economic system—saw their wealth permanently eroded.

“The state took action not to enrich, but to restore balance.”

(paraphrasing Tacitus, Annals VI.17)

This was not a bailout in the modern, moral hazard-inducing sense. The loans were conditional, targeted, and limited in scope. What Tiberius sought was not stimulus, but stabilization—to stop a systemic collapse that threatened not just the economy, but the social architecture of the empire.

In an order where credit supported land, land supported status, and status sustained governance, a frozen financial system was an existential threat. The 33 AD bailout was ultimately an act of political preservation, carried out through economic means.

Lessons from Ancient Rome for Today’s Housing Market

It’s easy to think of Rome as distant and irrelevant—columns, togas, dusty ruins. But the real estate crash of 33 AD reminds us that bubbles, speculation, and credit crises are nothing new. The mechanisms may have changed, but the human instincts behind them have not.

Rome’s mistake wasn’t just legal or financial—it was psychological. The belief that property values could only go up, that credit would always be available, and that the elite were too established to fail created a dangerous sense of invincibility. Sound familiar?

The Cycle Repeats

The Roman crisis shows us what happens when:

- Credit grows faster than confidence

- Legal interventions are rushed or poorly timed

- Land becomes a speculative asset instead of a productive one

- The financial elite forget they are vulnerable

Just like in 2008, or the rising housing tensions today in cities like London, Toronto, or Los Angeles, the story is not about buildings—it’s about belief. When belief in the system cracks, so does everything built on top of it.

History as a Mirror

Tiberius’s intervention may have been successful in the short term, but it didn’t change the underlying dynamics. The Roman elite returned to speculation within a generation. As always, memory faded faster than risk.

The question is: will we do any better?

From Rome to Today: Why a Crisis Always Finds the Unprepared

The Roman elite were brought down not just by bad laws, but by overconfidence—and a complete lack of financial margin. The lesson is timeless: in unstable times, the ability to save is the ability to endure.

If you want to build habits that protect you from uncertainty, start here: How to Start Saving Every Month: Mindset First, Numbers Second

For more on long-term resilience and Mediterranean-style money thinking, explore our personal finance articles.

References

Garnsey, P., & Saller, R. (1987). The Roman Empire: Economy, Society, and Culture. University of California Press.

Jones, A. H. M. (1974). The Roman Economy: Studies in Ancient Economic and Social History. Oxford University Press.

Kalle, S. (2005). “Roman Real Estate and the Debt Crisis of Tiberius.” Journal of Roman Economic History, 3, 45–67.

Scheidel, W. (2009). “Real Wages in Early Empires: A Comparative Approach.” Ancient Society, 39.

Suetonius, G. (1957). The Twelve Caesars (R. Graves, Trans.). Penguin Books.

Tacitus, C. (1996). Annals of Imperial Rome (A. J. Church & W. J. Brodribb, Trans.). Penguin Classics.

Temin, P. (2013). The Roman Market Economy. Princeton University Press.

The Island That Forgot the Clock: How Ikaria’s Relationship With Time Creates Longevity

Spanish Latte Recipe: Mediterranean Coffee Tradition Meets Modern Café Culture

Costa Brava Without the Crowds: Peaceful Towns, Coastal Trails, and Honest Local Tips